Rev. Dr. Willie F. Wilson, pastor emeritus of the historic Union Temple Baptist Church in Washington, DC, delivered the sermon for my ordination. His message, “Preaching Ain’t No Picnic,” emphasized that preaching is not a “cotton-candied, powder-pampered presentation.”

As a child, I attended a prominent Black Baptist church in Newport News, VA, led by a pastor who was both NAACP president and a member of the House of Delegates. From my earliest encounters with the gospel, I’ve understood preaching as a tool of freedom for the marginalized and liberation for the oppressed. Dr. Howard Thurman, in his groundbreaking 1949 book Jesus and the Disinherited, described the gospel as a message to, about, and for the “disinherited, disenfranchised, and dispossessed.” Similarly, abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke of Christianity’s transformative potential.

Dr. Frank Thomas’s How to Preach a Dangerous Sermon stands in this tradition. I found the foreword by Dr. William J. Barber II, The Terrible Joy of Dangerous Preaching, especially compelling. Dr. Barber argues that “dangerous preaching challenges our established notions about religion and its place in society.”

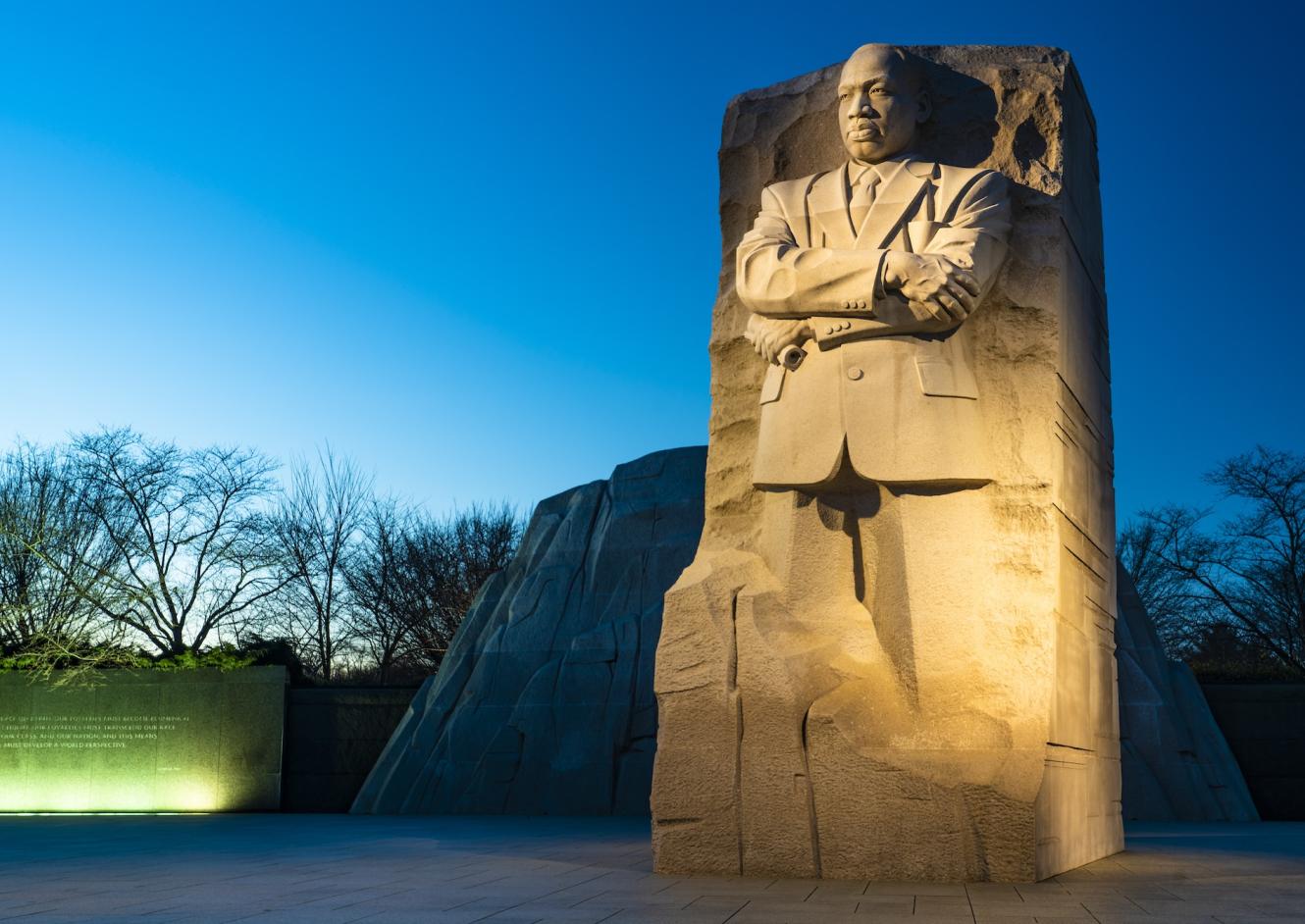

Recently, I had the privilege of sitting down with the brilliant and charismatic theologian Dr. Tokunbo Adelekan for a lively and insightful fireside chat. We discussed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s cultural roots, scholarship, visionary leadership, and commitment to civil and human rights. We also touched on the immense emotional stress Dr. King endured, never forgetting that he was assassinated at just 39 years old.

In my humble estimation, Dr. King embodied the spirit of Galatians 6:9, demonstrating a commitment to perseverance in the face of injustice. His ability to move hearts while challenging unjust civil laws was revolutionary. He often quoted the Negro spiritual, “Walk together, children, and don’t you get weary… there’s a great camp meeting in the promised land.”

In a nation increasingly polarized, what troubles me most is the relentless erosion of humanity at its core. While I am fully aware of this nation’s foundational contradictions, the ideals articulated in the Constitution have always provided some semblance of hope—even when ignored. Dr. King’s fight for diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as his challenge to the "othering" of people, revealed how bigotry diminishes the intrinsic divine value of individuals.

In Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, King laid out a prophetic vision for America’s future, calling for better jobs, higher wages, decent housing, and quality education. He proclaimed that humanity now possesses the resources and technology to eradicate poverty. Yet, his life ended not on the grand steps of the Washington Monument, but in the streets, marching for the dignity of sanitation workers.

This final chapter of his life reminds us that the work of justice is grounded in humility and the unyielding belief in the inherent worth of every individual. As we reflect on his legacy, may we be inspired to continue the work of preaching freedom and living out the gospel's transformative power.